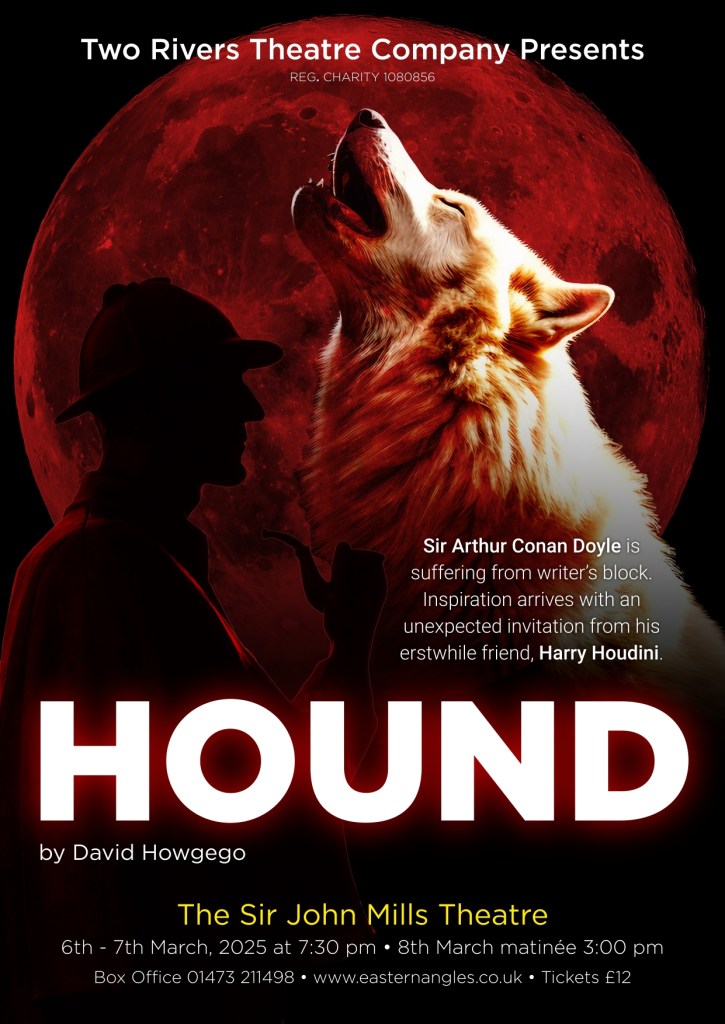

SIR JOHN MILLS THEATRE, GATACRE ROAD, IPSWICH. 6-8TH MARCH 2025

Thank you to Alan Stafford for this guest review

At the heart of “Hound”, a new play by writer/director David Howgego, is a fictional encounter between two iconic figures of the early 20th century – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, and master escapologist Harry Houdini. The pair had met several times in the past but their friendship had soured, and Howgego has imagined one final meeting where they attempt to patch up their differences.

The two meaty roles of Doyle and Houdini are played by Rob Aldous and Terry Palmer respectively. They bring this contrasting pair convincingly to life. The brooding, tweed-clad Scotsman, unwillingly shackled to the fictional detective who the public will not allow him to ditch. While no chains can hold the flamboyant American showman who forever seeks new and more hazardous challenges.

They fell out over the matter of spiritualism. Houdini, who knew how all the tricks were done, used his skills to expose any number of fraudulent mediums. While Doyle seemed on the face of things to be more gullible but, having lost so many of his family and friends in the Great War, was it any surprise that he would desperately want to believe anyone who might put him in contact with his lost loved ones?

A neat solidly constructed set serves as a variety of locations in the first half of the play, which we move between slickly with the odd lighting change, and the gentle guidance of Petra Risbridger as Doyle’s housekeeper, Mrs Hudson, who also acts as narrator. This worked so effectively, that we really didn’t need the couple of instances when characters told us which act or scene we were in and what period of time had elapsed. This could easily have been explained in the dialogue.

Other supporting characters were Stacey Palmer, as Houdini’s wife, and three sisters of varying intellect (played by Claire Turner, Christina Search and Nicky Seabrook) who, together with a dodgy vicar (Simon Hooton), contrive to fake seances with such devices as hidden wires, which they’re not always quite competent enough to operate.

After the interval, the rest of the play is in a single setting, with everyone gathered together as Doyle forensically reveals that not a single person is quite what they seem. Fakery and frauds abound and even some highly dramatic spirit writing is not as otherworldly as it appears. By and large it was crisply written and executed but, at this particular performance, several forgotten lines meant that the momentum occasionally dropped.

Overall it was an intriguing story, not least because of its basis in real-life events. And a rather wicked final exchange suggests that the credit for Sherlock Holmes’s observational skills should not be given to Doyle alone.

Alan Stafford